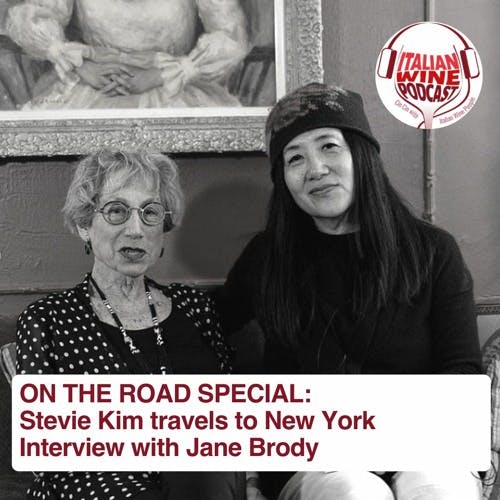

Ep. 1001 Jane Brody | On The Road Edition With Stevie Kim

On the Road with Stevie Kim

Episode Summary

Content Analysis Key Themes and Main Ideas 1. The groundbreaking career and legacy of Jane Brody as a science and health journalist. 2. The evolution of health journalism, particularly the shift towards ""service journalism."

About This Episode

The Italian wine podcast hosted by Italian wine Portuguese hosts discussed the importance of science in helping people live healthier lives and get out of negative coping. Speakers spoke about their experiences with women's health, writing books, and their desire to write a book. They also discussed their use of word processors in science and their desire to write a book for practical and practical resource for those who need help. They emphasized their passion for women's health journalism and their commitment to free content and suggest ways to donate.

Transcript

Welcome to the Italian wine podcast. This episode is brought to you by Vinitally International Academy, announcing the twenty fourth of our Italian wine Ambassador courses to be held in London, Austria, and Hong Kong, from the twenty seventh to the twenty ninth of July. Are you up for the challenge of this demanding course? Do you want to be the next Italian wine Ambassador? Learn more and apply now at viniti international dot com. Welcome to this special on the road edition hosted by Stevie Kim. Today, Stevie is in New York interviewing Jane Brody, a pioneer in health and wellness journalism. Listen in to them discuss her career and life after fifty eight years of groundbreaking work at the New York Times. This is a very, very special on the road edition, and we're in Brooklyn, New York to be precise when park slope with Jane Brody, an American journalist for our audience who are less familiar, Jane, would you mind introducing yourself to our audience? Because our audience is very wine centric, but also Italian, international, not necessarily Americans. So how would you explain who you are. Well, I am a retired now as but just as of one week. Right. I mean, that's I have spent my entire career as a science journalist, which means I write about scientific topics, mostly health related, and my goal was always to help people live healthier lives and and get more out of life than than they might otherwise if they didn't have the knowledge that I was trying to give them. When did you start your writing career and where did you on. I started my writing career right out of my graduate degree in science journalism at the Minneapolis Tribune in Minnesota. And after two years there, I got a job at the New York Times doing full time science writing with a focus on health, and I got the job by convincing the times that they weren't telling people enough that they needed to know to live good lives. And They asked me, but what do you mean? And I said, well, for example, if somebody has epilepsy at the in those days, in the nineteen sixties, if you had epilepsy, you couldn't drive, you couldn't marry, you couldn't go to a whole ton of things that normal people would be able to do even if your epilepsy was totally under control. And so I said, you need to tell people that life is possible. Normal life is possible. So that the rules get changed and so that people with this condition can live healthier. Well, on the basis of that little story, I got my job at the New York Times. And I've been there since nineteen sixty four and In nineteen seventy six, they asked me to write a weekly column, which really made a national reputation. It it was the first column in a newspaper that was devoted to health service journalism, service journalism on health. And nobody else was doing this at the time. They wrote gee whiz stories about the latest health discovery, the latest, you know, medicine, the latest fancy doctor, whatever. And but nobody was really writing information that would help people live healthier. And so that's the job that I acquired at the behest of an editor at the New York Times. It was interesting because the column originally started in the food section. Uh-huh. And, you know, where they ran food and wine and all those things that and the editor wanted something with that he considered more serious in that section. And so he came up with this idea to do a health column, and he asked me to do it. And I fought tooth and nail because I didn't wanna be saddled with something I had to do every week, but he said try it for three months. And after three months, you can come back and we'll discuss it. In three months, I came back. It was such a runaway hit from the very first very first. What were your first, like, a column? Well, this is interesting. I had to write four columns before they published one. They wanted to see how what they were gonna be like. And because I'm the deal I made with them is that I wanted to be allowed to write about any topic, health related topic. That I thought was important. So you had you had cut, blanche, like, free range. That's correct. I was not saddled with anything, but I put them to a true test. Now mind you, this was nineteen seventy six. The times the New York Times was considered the good gray lady. Which meant it was very old fashioned. But the first four columns that I that I wrote, which they wanted to see before they ran even one of them, I included a column on impotence Uh-huh, to put them through. When when was this? What's it? This was nineteen seventy six. Okay. Irrectile dysfunction didn't exist then as a phrase. Right. Right. Right. Right. Not even in medicine was it used. Oh, really? No. No. That's that comes way later. So you came out you came out with this topic. I wanted to see if they were gonna stick to their word that I could write about any topic. Right. Right. And did so they allowed you to write about that. They swallowed hard. And they published it. And what was the reaction? Well, it was like mind blowing to people, but I became what my colleagues used to call the sex editor of the New York Times I wrote about topics like impotence, like fragility, which is the other thing. The female version of impotence was called fragility. Mhmm. Nobody says that now anymore either. Right. But I got words into the newspaper. That had never been published in the New York Times. Words like penis. Right. When Masters and Johnson wrote their seminal work called human sexual response, they referred to the female organ as a vagina And the male organ as the male sexual organ, they never used the real word for this male sexual. And what year was this? Nineteen seven. Oh, this when you used the word penis. Yes. And I used the word penis. You are the first journalist who used the word penis? In the New York Times. Right. They published Amazing. I also was the first to have to get the word sexual intercourse on the page one of the New York Times. What did how did they describe it prior to that? God knows. Amazing. And the other phrase that that I was famous for, there was a study done by a woman named Cher Heights about women's sexual response in which she she showed that a very large percentage of the majority of women do not reach orgasm with just what she called penile thrusting. Right? Well, That that made that made me world famous that gave me no thrusting into the New York Times. And one of the editor who had me, writing this column said, they don't really wanna run this. And I said, Well, show your wife. He took it home. He took the article home, showed it to his wife who said, do you realize how many divorces happen because men don't know this? Right. Right. So it's you had some alliance the wife of one of the major editors at the at in the newsroom. I mean, he was always on my side, but he had higher ups also to deal with. So, I mean, so in the end, how many years have you worked for New York Times? How many years? Yeah. How many years. I started in nineteen sixty four. Right. And I just finished now in nineteen two. A two thousand and twenty two. Yes. At fifty eight years. Yes. Fifty eight years. Wow. Is that a record? For New York Times? I don't know. Honestly don't know. Right. I don't really know. Most most people now are not sticking around that long. They're really not. Anytime that I thought about quitting, I said, why would I quit? I have the best job in journalism. That you could have. I didn't and before I wrote all this health stuff, I also wrote a lot of natural history and I loved that. That was my passion. So I wrote about everything from crows to bears to frogs, to environments like heat bugs, stuff like that. And I made up assignments for myself that got me to places that I wanted to go to. Were there a lot of women? I was the only woman in my department for a long time except for the the so called secretary. So your your department meaning science news. Yeah. How many were the others? There were about seven of us and just one woman, and then eventually they hired another woman, but they moved her to Washington. They didn't really want her there. You know, women came into science to health journalism. Women came into health journalism because men weren't doing it. There was there was an open door. Weren't doing it because there were uninterested or It just it wasn't it wasn't the scene yet. Right. You know, believe it or not, a lot of things that we talk about now at at seems so normal in in health issues were never ever written about anywhere. Maybe it may be in some of the women's magazines. The men wanted to write gee Wiz stuff. You know, the the discovery of heart transplants. Right. Right. You know, the something. Big splashy. Big splashy things. And Right. But no nobody was writing the the kind of stuff that The women when we went to science writing seminars and health issues, we got related to health issues. The vast majority of the journalists were women because that was the field we could go into without a competition. We didn't have to kick a man out of a job in order to get one, which was a big deal. And it's it's an interesting history actually of of science journalism and, you know, the men caught on because it was very popular. So you I mean, because also your column was syndicated. Right? Well, they weren't syndicated in the sense that I got paid for every newspaper that ran. Probably New York Times had a what they call a news service And when many newspapers bought the New York Times news service Right. And they could run anything that the Times put out. And but but the people who wrote that stuff did not get paid for it unlike syndicated columnists who got paid for it. That's the difference then. So we just got straight salary. So so in reality, your audience, your readers Yeah. Are from the entire country, not exclusively, you know, territorial. They're not exclusively anywhere. Thank you for listening to Italian wine podcast. We know there are many of you listening out there, so we just want to interrupt for a small ask. Italian wine podcast is in the running for an award. The best podcast listening platform through the podcast awards, the people's choice. Lister nominations is from July first to the thirty first, and we would really appreciate your vote. We are hoping our listeners will come through for us. So if you have a second and could do this small thing for us, just head to Italian wine podcast dot com from July first to the thirty first and click the link. We thank you and back to the show. So how how do you how did you keep up with your did you have, like, a report with your readers? Oh, wow. Do they write to you? Oh, yes. I mean, this is this you realize it started long before there was an internet Alright. Long before we had even a word processor let alone a computer. The the really fun story about about this is that when the times introduced word processors into the newsroom, they very did a very smart thing. They brought it for the first the first trial into the science department because they figured science writers would be less afraid of these toys. Oh. Then the rest of the reporters who were used to writing you know, on a yellow pad. Was that true that? I I I would think so. Oh, yes. So when was even word processor invented? I I don't even I I'd you'd have to look it up, because I don't I don't really know, but I do know that my sons grew up with them because I remember well? Are you sure? No. No. No. They were about ten or eleven or twelve. They were young. Maybe eleven. Yeah. When they decided to add memory to the to the word processor. I was I was hysterical. I was afraid they were gonna break this thing. They took the back off it and and added stuff inside it and close it up again and it Well, who is that? Erica Lauren, both of them. Both of them. Yeah. So, you know, they were maybe that's forty years ago now, more than forty. So how did you keep up with the with the correspondence is with your readers? Well, they they will. They sent you sent any, like, a letter. You get a box full of letters. They sent letters. I got mail all the time. And did you reply to all of them? I replied to a lot of them, but, you know, I couldn't reply to all of them. I didn't have secretary. No. You didn't have help. Not even like interns or anything like that. Not to answer my mail. There were interns who would occasionally do some Xeroxing for you. Right. That was that was what we did. Xeroxing. If I wanted this save a journal article, for example, in a file, we had to Xerox it and file it. So did you always, like, from the get go? You had to physically go to the office. Oh, yes. Was that correct? Yes. Physically go to the office five days a week. And yes, you could do some stuff in between, but mostly it was just in in office work. It was all in in office work unless you were on the road researching something and then then it wasn't inside the office. But all the writing took place basically on a typewriter until we got word processors. Right. Right. But the interesting thing about the word processors, or they introduced it into the science department. And within a few days, we were so excited about this toy that we could, you know, we we used to if you needed to make a change in your copy, you had to start over again and retype it. Whereas with the word process, so you could just stick it in where you wanted it and move stuff around. And so we were like problematizers. For the newsroom. All the science writers would go around saying, you're not gonna believe how great this is. Right. Right. Right. You're like the, yeah, evangelist. Evangelist. But there was a downside to all of this, and that is they used to crash. I lost a whole chapter of a book that I was writing when the computer when the word processor crashed. Who the hell knows what goes on inside them? But I could never retrieve it. So listen, that's a good segue to, books. Your books. Mhmm. So you didn't only write for New York Times. You also wrote books. And that happened. When did that start? That happened. Because within three years of my writing the column, so nineteen seventy nine now, publishers wanted to publish a book of the column and the time said no. Are they saying no? They owned it. They owned them. They said if anyone is gonna publish it, we will. But what happened was that the primary publisher w w norton who really wanted me to write for them. And they said, well, we don't just want your columns. We want Jane Brodie author. And so what what would you write? What kind of a book would you write for us? I said, I don't know. And they said, well, what's your most popular column topic? And I said nutrition. And that's when you wrote the nutrition that's when I wrote the nutrition book. They said, okay. And that was a best seller. And then I got letters from readers of the book asking me, okay, you told us how we should eat. Now tell us what to make. And so then I wrote the good food book, which is a book of recipes. How long did it take you to write the nutrition book? Yeah. One calendar year. I wrote two chapters a a month. Don't ask It was insane. Wow. I would get up at five o'clock in the morning, and I would ride for an hour and a half, then I'd go out and do my jog, and then I would come back and get my kids out, give them their breakfast, get them out to school, and then get myself together, and get to the work. So, you know, you you, not only pretty good health, good way of living. You also practice. Right? Always. And you are a true believer in what you say. So tell me, I'm a true believer. A little bit fanatical. I have to be honest. No. I don't. Because I don't have that discipline. I don't think many people do, but give give give me your typical routine. Yeah. I I do not consider myself fanatical except that I do believe it you you should not be making the decision every day to exercise. You just do it. I don't just I don't wake up in the morning and say, oh, I don't feel like going out today. Maybe I'll maybe I'll just sleep an extra hour and a half. And that that's like ninety nine percent of people. Well, this is what I've been trying to tell them all these years that that's not the way to live because every bit of evidence, every bit of evidence says we evolved on the move. We have to keep moving if we want to keep living. Mhmm. And that's that's that's a a given. You know, it was a fellow who lived across the street from me who retired. He was a he was a bricklayer or something like that. He he retired and he just sat in the house and before I knew it, he was in a wheelchair. I mean, It's that's not what your body is meant to do. One of my favorite quotes now from a doctor, I know, said sitting is the new smoking. I mean, obviously, we sit. We have to sit. We sit at our jobs. And most of us sit at jobs. Absolutely. Very few people have physically active job and and fewer and fewer at with time because those kinds of jobs are being taken over by robots Give me your, like, typical schedule. My typical schedule is my alarm goes off at five thirty. Every day. Yeah. You I have a dog. Dog has to go out. I wanna do my little ablutions before I take him out. I'm out with him between seven and seven thirty every morning. And we come back about eight thirty. Give him his breakfast, and then I go off to the pool and swim. I go to a y m c a every day. In the summer when I'm not here, I swim somewhere else, but I swim every day. How long do you swim for? Well, I And you're just doing laps. I'm doing laps. Yeah. I'm swimming laps. I swim at least a half an hour and I sometimes forty to forty five minutes depending upon the nature of the day and the nature of the pool and whatever. Oh, weren't you afraid and you did this even during COVID or the pools were closed? Well, the the all everything closed down. Mhmm. From mid March twenty twenty, the y opened its pools on October first twenty twenty with very strict protocols. And you had everybody has his own lane, and they even varied where you got into the pool so that you didn't get in. You weren't next to anybody else. I mean, this was before anyone had a vaccine. Well, I still went to the pool. I signed up immediately as soon as they made it possible. And But what did you do from March to October? We we tried at first, we tried my my pool friends and I tried right biking. We have a a nice park right near my house and so on. We bike around the park. It was so cold. It was cold in March, and they gave up. So I walked more and I I just did whatever I could. You know, if you have stairs, those are that's a very good kind of so I just can just run up and down the stairs. Then I I always run up and down the stairs, so it's nothing nothing unusual for me to do. And then you do you go to the pool and that's it now? Because when I met you first time, you used to you were crazy about power walking. Right. Well, we weren't power walking in the sense that nobody was nobody I don't remember what year that was, but but we walked every morning. Yeah. I guess I walked with well, before We walked at six o'clock. My friends are still walking at six o'clock. Yeah. And then I got the, you know, the dog, and it was really difficult to get everything in, the six o'clock, and the dog, and then the pool, and then, you know, and then it then worked. And my knees got bad. I played a lot of tennis. Right. Right. I played a ton of tennis. I used to play tennis every day. And when when my knees got replaced, I guess no. I still walked. I I walked after that, but it was it really became a problem. Walking became a problem. So listen Jane, I want to talk about your latest book. So the nutrition, the recipes, the food, kind of book after that, after all those hugely successful books. You wrote guide to the great Beyond. What what is this and why did you write? Well, read the subtitle out loud. It says a practical primer to help you and your loved ones prepare medically. Legally and emotionally for the end of life. See, it it occurred to me that and I I wasn't old when I wrote that. I mean, I it was two thousand and nine, I think, that people things happened to them and they weren't prepared to deal with them. They didn't have anything. They didn't have anything in place. They didn't have directions for doctors as to how I should be treated if such and such happens to me. Not everybody wants be all an end all of medicine. Some people say, you know what? If this if I get to this point, I don't want you to do anything. That's the kind of information that I felt people should have, and they should understand what their options are. And and how to make use of them and how to put them in places. This is a very practical, a practical book to help people cope with their own and, and their families and their loved ones issues. So it's both for, the, let's say, the elders, but also their family. It's for everybody. And believe me, if you're eighteen years old or older, you should have put it in place the information that's in that book because Before your eighteen, your parents make the decision. But after eighteen, you have the right to make your own decision. And that so it's really important. And, you know, my husband died a year after that book was published. Twenty ten, and we used the information. I mean, he He had already told me when he was diagnosed with a metastatic cancer that he did not want any fancy treatment. And so following the diagnosis, we just said exactly that this is what you want, this is what you're gonna get. And His his body was left to science. Mhmm. So that, medical students could practice on him. That's what he wanted. Right. And it wasn't my decision. I mean, I would have made the same decision, but it was his decision and we just put it into practice. And that's what I'm telling people in that book is the person whose life you are managing has a right to say what they want out of life. I interviewed an another journalist whose husband had advanced Parkinson's disease Mhmm. To the point where he couldn't do anything for himself, and he just did not want to live that way. And she had to follow what he wanted, and she did. When he said, I've had it and the only legal the only legal way to end his life where he lived was to stop eating and drinking. So that's what he did. She said it was very difficult to watch, but it was in his honor. And that's really it. We honor your loved one's wishes. And I I think it's really important. So, are you are you religious or spiritual? No. I would say I'm spiritual in the sense that I believe that people should have a joy of life. I mean, I'm a very here and now person. I don't believe in a hereafter. I don't think they're I don't think we're going anywhere. I don't think anyone's gonna take look after us once we're gone from this earth. And I am a spiritual person, but I have not been a religious person for a very long time. I think I really really, I was raised as a Jew. I I went to Hebrew school. I even was fluent in Hebrew Mhmm. At one point. But when I married a man who wasn't Jewish and no rabbi would consider marrying her, I said, Uh-uh. Richard was agnostic. No. Well, he became agnostic, but he was raised as a lutheran. And definitely, he was much more of a church goer than I ever was of a synagogue goer. I love the rituals of Judaism, but I practice it. Service and Jane. I'm going to ask you one last question because, you know, you know, I'm wine centric. And you're a science journalist. So what is your opinion about wine and health? Well, there's no question. That if you look at the study, it's very, very straightforward. Alcohol in general makes a u shaped curve. If you you don't drink at all, you're over here on the curve. If you drink one glass a day, your risk of death goes way down. But if you get to more than two or three, it goes way up. Per day. Yes. So one glass a day of especially wine, but alcohol in general, alcohol in general makes this j shaped curve. Like that. Of all the alcohols, wine is the most beneficial, and red wine is especially the most beneficial. Now, what will you do with your time? You're all your extra time? I haven't made a commitment yet. Right. I'm thinking about writing essays and because it's hard to take the writing out of a writer. Yeah. It just it's just in my blood. It's all done what I've done all my life. Very hard for me to just sit back and say, okay. I'm not gonna write anymore. But you just told me in the very beginning when I got here, it's like, this is the last book you would have written. I'm not doing another book. It's no more books. I don't really wanna the publishing industry is too too challenging now. Mhmm. I agree. And I just don't I just don't wanna do another book. I don't wanna deal with all the rigmarole that's involved in doing a book. And it's a lot of rigmarole. Mhmm. You have to be passionate about it. I was very passionate about this. I thought of the title of this book when I was swimming. Mhmm. I had thought about doing this book for two years before that. But when I thought of the title, I said, okay. I guess I gotta do it. I have to do it. But I don't have that kind of I have to be passionate about the subject. Otherwise, I I won't. I won't do it. But at the moment, I don't really wanna write a book, and I don't think I will. I may write some essays. I I like the kinds of essays that I would do, if I was giving a lecture, which I'll be giving on my last lecture in a in a week. Where? Whereabouts? Actually, I'm on Wednesday. No. It's some organization asked me to do a talk on Because used to travel a lot too. I did. It traveled a lot. As a speaker. I'm so glad I don't have to do that anymore. I really am. I have a whole cabinet of just travel preparations. And I said, why am I saving this stuff? Barbara. That's it. It's a wrap. We that was Jane Brody. Thanks for listening to this episode of Italian Wine podcast. Brought to you by Vineetli Academy, home of the gold standard of Italian wine education. Do you want to be the next ambassador? Apply online at benetli international dot com. For courses in London, Austria, and Hong Kong, the twenty seventh to the twenty ninth of July. Remember to subscribe and like Italian wine podcast and catch us on Soundfly, Spotify, and wherever you get your pods. You can also find our entire back catalog of episodes at italian wine podcast dot com. Hi, guys. I'm Joy Living's Denon. I am the producer of the Italian wine podcast. Thank you for listening. We are the only wine podcast that has been doing a daily show since the pandemic began. This is a labor of love and we are committed to bringing you free content every day. Of course, this takes time and effort not to mention the cost of equipment, production, and editing. We would be grateful for your donations, suggestions, requests, and ideas. For more information on how to get in touch, go to Italian wine podcast dot com.

Episode Details

Related Episodes

Ep. 2525 Daisy Penzo IWA interviews Veronica Tommasini of Piccoli winery in Valpolicella | Clubhouse Ambassadors' Corner

Episode 2525

EP. 2517 Sarah Looper | Voices with Cynthia Chaplin

Episode 2517

Ep. 2515 Juliana Colangelo interviews Blake Gray of Wine-Searcher | Masterclass US Wine Market

Episode 2515

Ep. 2511 Beatrice Motterle Part 1 | Everybody Needs A Bit Of Scienza

Episode 2511

Ep. 2505 Ren Peir | Voices with Cynthia Chaplin

Episode 2505

Ep. 2488 Juliana Colangelo interviews Jonathan Pogash of The Cocktail Guru Inc | Masterclass US Wine Market

Episode 2488